- Home

- Benjamin Wardhaugh

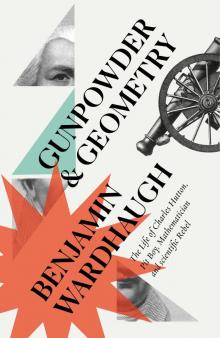

Gunpowder and Geometry

Gunpowder and Geometry Read online

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © Benjamin Wardhaugh 2019

Cover illustrations: engraved illustrations of Artillery Carriages © bauhaus1000/Getty Images; engraving of Charles Hutton © Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo.

Benjamin Wardhaugh asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008299958

Ebook Edition © February 2019 ISBN: 9780008299972

Version: 2019-01-11

Dedication

In memory of Jackie Stedall

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1 Out of the Pit

2 Teacher of Mathematics

3 Author

4 Professor

5 Odd-Job Man

6 Foreign Secretary

7 Reconstruction

8 A Military Man

9 Utility and Fame

10 Securing a Legacy

11 Controversies Old and New

12 Peace

Epilogue

Notes

Select Bibliography

Image Credits

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

1

Out of the Pit

August 1755. Newcastle, on the north bank of the Tyne. In the fields, men and women are getting the harvest in. Sunlight, or rain. Scudding clouds and backbreaking labour.

Three hundred feet underground, young Charles Hutton is at the coalface. Cramped, choked with dust, wielding a five-pound pick by candlelight. Eighteen years old, he has been down the pits on and off for more than a decade, and now it looks like a life sentence. No unusual story, although Charles is a clever lad – gifted at maths and languages – and for a time he hoped for a different life.

Many hoped. Charles Hutton, astonishingly, would actually live the life he dreamed of. Twenty years later you would have found him in Slaughter’s coffee house in London, eating oysters with the president of the Royal Society. By the time he died, in 1823, he was a fellow of scientific academies in four countries, while the Lord Chancellor of England counted himself fortunate to have known him. Hard work, talent, and no small share of luck would take Charles Hutton out of the pit to international fame, wealth, admiration and happiness. The pit boy turned professor would become one of the most revered British scientists of his day.

This book is his incredible story.

Newcastle upon Tyne occupies a fine site for a town: a long south-facing slope, down towards the river. The Great North Road runs through it: 90 miles north to Edinburgh, 250 south to London. And the river joins the town to the world. As the old song goes,

Tyne river, running rough or smooth,

Brings bread to me and mine;

Of all the rivers north or south

There’s none like coaly Tyne.

By the time coaly Tyne passes under the bridge at Newcastle it has seen the Pennines and the wild country of Northumbria: land fought over by the Romans and the Picts, the English and the Scots. If the water had once been dyed with their blood, by now it was dyed with coal.

The town was spacious and populous. Only three English towns were bigger; but still Newcastle was no sprawl early in the eighteenth century. Just five main streets within the old town walls, and open country beyond them to east and west.

We know next to nothing about Charles Hutton’s parents, Eleanor and Henry. It’s probable they moved to prosperous, growing Newcastle from elsewhere: possibly from Westmorland, on the other side of the Pennines.

Eleanor and Henry seem not to have prospered in any tremendous way in Newcastle, though neither were they at the bottom of the heap. Henry was a ‘viewer’ in the collieries: something less, that is, than a land steward or estate agent, and something more than a manual labourer. Viewers were literate, numerate men who kept the colliery’s records and compared notes with their colleagues at neighbouring mines. They measured and calculated rates of production, kept an eye on how fast the pit was filling with water and how well the pumps were coping. They allocated labour, planned, inspected. Some stayed up at night to catch coal thieves.

Viewers were expected to be down the pits daily, but also to see the estate agent daily. They faced two very different worlds: the wealthy owners and the men who hewed the black diamonds out of the rock beneath their feet. They had responsibility and power; some abused it, keeping owners ignorant about the mine work. Many used their position to command high fees. The coal industry was expanding, and new shafts and new mines depended on the advice of experienced colliery viewers. High-end viewers had their own assistants and apprentices: minor deities in their own field.

One source says Henry Hutton was a land steward for Lord Ravenscroft, a step further up still. We don’t know if it was true, and it may just be a garbled reflection of the fact that he oversaw a mine or mines on that nobleman’s land in Northumberland. Either way, he was a man who had a good deal more than the very minimum.

By 1737 Eleanor and Henry lived with their children – three or four boys, perhaps more – in a thatched cottage on the northern edge of Newcastle. Nineteenth-century historians would be rather sniffy about this ‘low’ dwelling (low, probably, both literally and metaphorically); but compared with the cottages of the miners themselves it was luxury. Thatch, indeed, was a luxury, as was the ability to live more than a stone’s throw from the pit mouth.

Just as Henry Hutton worked at – was – the interface between landowner and manual workers, his house stood on the edge in more than one sense. Sidegate, their street, was one of the first to burst out of the still intact medieval town walls, and while open land surrounded it on both sides, a stroll down the hill took you back to the bustle of Newcastle. Away to the north it led across the Great Northern coalfield, engine of England’s prosperity.

The ‘low’ cottage of Hutton’s birth.

Charles, Henry’s youngest son, came into the world on 14 August 1737. A fortnight or so later his parents took that stroll downhill to the parish church of St Andrew’s, just inside the town wall – stubby tower, Norman interior, bright new set of bells – and he was baptised.

For a few years, all was well. There were games with other children in the street; there were fights. Ladies liked little Charles; they thought him uncommonly docile and good-natured.

The Huttons sent some, perhaps all, of their children to school. On the walk from their cottage to St Andrew’s they passed Gallowgate (actual hangings were a rarity by Hutton’s time: one every few years, if that). And on the corner of Gallowgate a house stuck out awkwardly into the street. In it an old Scots woman kept what the usage of the day optimistically called a school. That is, she took in a few of the local children and endeavoured to show them how to read, with

the aid of a Bible. Charles Hutton remembered her as no great scholar; when she came to a word she couldn’t read, she would tell the children to skip it because ‘it was Latin’. But he did learn to read.

In the summer of Charles’s sixth year his father died. Swiftly his mother remarried; with several children to keep, the youngest of them five years old, there was perhaps little real choice. Their new father, Francis Frame, occupied a lower station than Henry Hutton. He was an ‘overman’ in one of the collieries: a labourer, but one who was also employed to superintend the others. Not necessarily literate, not necessarily numerate: there was a system of marks and tally sticks to avoid the need for that. His pay might have been half that of a viewer, and he basically worked underground. And he had to live near the pit. Shifts might start in the small hours, even at midnight, and you couldn’t be walking a mile or two in the dark just to get to the colliery. The family left the house in Newcastle, and moved north into the coalfield itself. And coal changed from a distant background, a what-my-dad-does, to an immediate daily reality for Charles Hutton.

Hundreds of thousands of tons of it went down the river each year, and the market was growing all the time. Over the course of the eighteenth century the industrial revolution and the steam engine would increase Britain’s hunger for coal to stupendous levels. As the coal trade grew it expanded away from the river, north and south; new collieries were opened and new wagon routes built to serve them. Landowners gambled huge sums on the chance of reaching a profitable seam, but they also told themselves – and believed – that they were doing a public service: providing jobs, providing coal.

The so-called Grand Alliance of colliery owners was sinking new pits on north Tyneside, where coal to last hundreds of years lay undug. The villages there – Jesmond, Heaton, Long Benton – would now be the Hutton family’s world. This was the true coal country. The landscape of the Great Northern coalfield was all pits and pit villages; the hills and the fields, the river and the tearing clouds formed little more than a scenic backdrop. Streams were everywhere, making steep little valleys and shaping where you could build, where you could walk. And where you could dig. The wet got into the pits, and a mine on north Tyneside could raise a dozen or more times as much water as it did coal. Horses plodded around horse-gins to wind the ropes that brought it all up, and unwind them again to send the men down.

The members of the Grand Alliance were technophiles, and they installed the new atmospheric engines designed by Thomas Newcomen – forerunners of the steam engine – at their pitheads to do some of the winding work. The machines were cheaper to run than horses, but they were loud, and they added to the noise, the smoke and the dust. It’s hard to get a sense of it today, now that the pits are closed and the collieries built over with smart modern houses. On a clear day you can see down from Long Benton, where the Huttons worked, to the spires of Newcastle’s churches, and beyond to the rolling country south of the river. There are still some open fields nearby – playing fields, now – and the long line of the old wagonway, down towards the river, remains as a peaceful footpath; birds sing in the hedges.

In the 1740s it was a very different place. The wagonway had wooden rails, and the Long Benton colliery and its neighbours ran an endless procession of horse-drawn wagons on them, taking the coal down to the staithes at the river’s edge. The spires of Newcastle may have been visible through the clouds of coal dust and smoke, but they represented a distant, unattainable world.

Nearly all collieries provided housing for the underground workers, and the Huttons presumably lived in such a dwelling. Long gone now, the miners’ cottages were packed in tightly, in rows as close to the pit mouth as could be managed. They were drab and uniform; two rooms was usual, with an extra chamber in the roof. Quite a few had gardens for vegetables, or even a pig or cow, or some hens. The tradition on the Great Northern coalfield – at least later – was for growing prize leeks.

The pit villages were isolated physically and socially. It was an unusual environment, supporting an unusual kind of work. The miners made a close-knit world, with massive revelry at weddings and christenings (and any other excuse): roaring bagpipes and roaring men; hilarious, vulgar, open-hearted.

Middle-class visitors typically found the miners and their families shocking, barbarous, uncivilised. Translated, that probably means miners’ pubs were noisy, their homes not absolutely spotless, and their knowledge of scripture of a slightly less than prizewinning standard. The miners’ world may have been rough and simple; squalid it was not.

They were proud of their appearance. Like sailors, you could tell the miners anywhere by their clothes: checked shirts, jackets and trousers with a red tie and grey knitted stockings. Long hair in a pigtail. And of course the pall of coal dust, almost impossible to wash out completely. Rings of it circled their eyes, and it made the cuts and abrasions of underground work heal into distinctive blue scars.

Charles Hutton would remember his stepfather Francis Frame as a kind man. But he was not Lord Ravenscroft’s land steward, nor anything like it, and there was no avoiding the fact that the family’s expectations had fallen. There had probably never been any question about what work the boys would go into, but if there had been hopes of climbing the ladder to become viewers and overmen they probably now hoped for nothing more than the status of plain coal hewers.

And by the age of six, or certainly by the age of eight, little Charles was old enough to start work. One report says he spent some time operating a trapdoor in the pits. For a miner’s lad this was typical entry-level work, done by the youngest boys. Different areas of the pit were isolated from each other by trapdoors, usually kept shut to make sure the air flowed where it was supposed to and reduce the risk of gas build-up and explosion. Each trap had a boy to pull the cord that opened it, and shut it again after men or coals had passed. Boring but crucial work; mines blew to smithereens if a trapper lad fell asleep on the job and let the bad air reach the candles. Solitude, silence and darkness worse than any prison. You learned not to fear the dark.

You learned much else, too; starting in the pits was not so much a training as total immersion in a culture. The all-male environment had its traditional ways: ancient facetiousness and long-lived jokes; bravado in the face of shared danger. Men died in the pits, often: candles in the gassy dark (there were no safety lamps as yet); shaft collapses; suffocation. Firedamp and chokedamp, the miners called the bad airs, and they were especially common in the northern pits. By the 1750s coal owners were asking the newspapers not to print reports of pit explosions; they were bad for morale, bad for trade.

So you learned the feel of the mines and the smell of the different airs, good and bad. You gained the true pitman’s instinctive sense of danger. You also learned to cling to the rope that pulled you up and let you down the shaft. Shafts could be a few hundred feet deep, and there were no cages to ride in. You just clung on, with your leg through a loop of rope. If your hands grew tired, you died. If the horses pulling the rope were startled and bolted, you died. Eventually that would happen to Francis Frame, in an accident at Long Benton colliery after Charles had left. Over the course of a life’s work in the pits your chance of dying in an accident was probably as high as one in two.

By the time the exploitation of children in the pits became the subject of official inquiry – in the 1840s – it had attained the proportions of a national disgrace. Boys were working twelve- or even eighteen-hour shifts that started at midnight; they were seeing the sun on only one day a week and they were getting rickets, bronchitis, emphysema. They were prostrated by exhaustion and they were not growing properly.

There’s no real reason to suppose conditions were better in the eighteenth century, but Charles Hutton was spared the very worst of it. There were schools in some of the local villages. Some pit villages had them, too, with practice varying seemingly from pit to pit: near-universal illiteracy at one; school provision built into the miners’ contracts at another. Hutton attended schools. He

was bright, and neighbours were already saying the lad could go far, urging his parents to keep him at school. Kept in school he was: the hope of his family, even while his brothers went down the pits.

It must have made for some friction at home and in his village. The few pennies per day he would have earned on the trapdoors might not have been a real sacrifice for his family. But the fact that others were being prepared for a life in the coal mines and he wasn’t must have made for a difference, and not perhaps a pleasant one.

About this time Hutton injured his arm. The story he would tell many years later involved variously an accident or a quarrel with some children in the street. Nothing more than ordinary horseplay, perhaps, but by the time he confessed it to his parents the bone wouldn’t set properly, and it left him with a lasting weakness in his right elbow. Another reason to train his mind rather than his hands, at least for now.

A schoolteacher named Robson taught him to write, at a school a short step across the hill in the village of Delaval. Hutton may well have studied from a new, locally produced grammar book. Written and printed in Newcastle, Anne Fisher’s New Grammar promised to teach spelling, syntax, pronunciation and even etymology through its carefully graded series of exercises. Unlike other grammar teachers she kept it practical, and there was time set aside in her programme for taking dictation from a newspaper read aloud (the London Spectator was her preference) as well as spot-the-mistake games. Like every textbook author, she hooked her learners with aspirational promises. By the time you were done, she said, you’d be able to write as correctly as if for the press, engage in polite and useful conversation, and compose a properly styled letter to any person of quality. London and its cosmopolitan values were never far from her thoughts. Yet she had her other foot firmly in the North, and her correct pronunciation was a distinctly northern one. Say the following words, she advised, as though the o was a u: Compasses, Conjure, London.

Gunpowder and Geometry

Gunpowder and Geometry