- Home

- Benjamin Wardhaugh

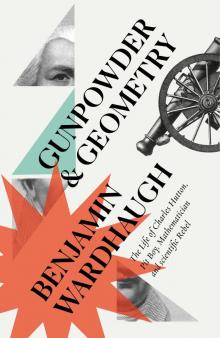

Gunpowder and Geometry Page 17

Gunpowder and Geometry Read online

Page 17

The governor, the inspectors and the professor of fortification were now provided with houses outside the Academy precincts; others found their own accommodation. The Cube House was purchased from Hutton and became an infirmary. But there was then an unexpected embarrassment about the village of houses he had built beside it. During a visit to the new Academy the King noticed that the view from it down towards the barracks was blocked by ‘some new houses’. ‘Let the whole be purchased, and the obstructing parts removed,’ decreed the monarch. Hutton agreed to accept a valuation determined by a surveyor from the Board of Ordnance, and their Mr Wyatt settled on twenty years’ worth of the total rents Hutton was receiving. Six of the houses were demolished at once, though the rest remained; precisely where Hutton and his family now lived is not clear.

On top of this, Hutton was tiring of his work at the Academy. He was in his thirty-third year there, and with no prospect of peace in Europe the disruption of war was perhaps becoming hard to bear. Just a year later, in June 1807, he was granted permission to retire, with a pension of five hundred pounds per year. The sum was large enough to be a compliment; more, indeed, than he had been paid as salary for much of his time at Woolwich. He agreed to stay on as examiner of both cadets and new masters, and to provide advice when it was needed.

Rather than stay near the Academy, though, he moved into London, close to the Inns of Court where he had long kept rooms. His new town house on Bedford Row was near both the British Museum and Somerset House, where the Royal Society met (if that still mattered): close to London’s intellectual centre, and to some of his friends.

He was affluent; the sale of his land and houses on Woolwich Common had left him with what contemporaries reckoned a small fortune, perhaps forty thousand pounds: equivalent to well over a hundred years of his salary at Woolwich. Some he invested in a bridge-building project that failed to pay any dividend for many years, but the rest brought income at something like 5 per cent. Together with his pension, then, he had around fifteen hundred pounds a year, at a time when Jane Austen’s Dashwoods were making do with a third of that in their cottage on the Barton estate.

It was a pleasant house, the street broad, light and airy. A regular round of visits and visitors soon formed, and the house was crammed with books. The Huttons had two pianos; Isabella certainly played, and perhaps Margaret too. Isabella dearly loved a play, and Hutton appears to have been fond of the theatre as well. In 1809, rising prices at Covent Garden Theatre led to riots, and a committee formed to raise subscriptions and build a new theatre. Hutton sat on the committee.

Hutton was seventy at his retirement; his own Dictionary contained the official table of life insurance premiums, and it only went up to the age of sixty-seven. One of the activities to which he devoted himself more and more assiduously during his last decade at Woolwich and in his retirement was the securing of his intellectual legacy.

This he did first through people. At the pinnacle of the philomath network, the retired holder of a key role at a highly visible institution of national importance, still a Fellow of the Royal Society even if he no longer attended its meetings, and a Fellow of three foreign societies, Hutton had often been asked to recommend mathematicians for teaching jobs and other work. He plied this trade well, and any number of provincial mathematicians were plucked at his word from the ranks of The Ladies’ Diary and installed in positions of prestige and responsibility. Lewis Evans, a country schoolmaster who got to know Hutton through the Diary, became a mathematical master at Woolwich, though he had to be asked more than once. David Kinnebrook, another Diary contributor, became an assistant at the Greenwich Observatory. Charles Wildbore, a contributor to The Gentleman’s Diary, became its editor. Edward Riddle moved from private teaching in Newcastle to become master of the Trinity House School, Newcastle, and then master of the upper mathematical school at the Royal Naval Hospital, Greenwich. John Bonnycastle, yet another Diary man, became Hutton’s first assistant at the Royal Military Academy. And it was not only Diary contributors who benefited. Margaret Bryan, a schoolmistress, received a testimonial and crucial encouragement for her book about astronomy. Major Edward Williams and Lieutenant William Mudge of the Royal Artillery were recommended to conduct the Trigonometrical Survey of Great Britain; Mudge (the same Mudge whom Hutton had once turned back into the lower academy until his mathematics should improve) later became governor of the Royal Military Academy. Sir John Leslie was recommended for the professorship of mathematics at St Andrew’s, and later for that at Edinburgh; the young Charles Babbage was recommended (unsuccessfully) for mathematical professor at the East India Company’s college in Hertfordshire.

Hutton felt a sense of duty about all this: ‘serving and encouraging very able and worthy persons, and … supplying useful institutions with good and proper teachers’, as he put it. But, like much that he did, it also drew some attention to himself, built his own reputation; and the more he did in this kind, the more he was able to do.

All these men and women, in turn, owed Hutton something and could be relied on to do at least a little to promote his interests and serve his legacy: for instance by praising and promoting his books and disparaging their rivals. Such things mattered. Back in 1788 there had been a quite extraordinary fracas when a jealous rival of schoolteacher Lewis Evans put it about that Evans had ‘in public company’ dispraised Hutton’s Guide. Evans not only wrote to Hutton in the greatest haste to deny the charge; he also organised a joint letter from the governors of his school testifying to the same effect. Patronage worked both ways, and damaging Hutton’s reputation – or being thought to have done so – could have been costly indeed for Evans.

The most important promoter of Hutton and his work was a bookseller and mathematician who rejoiced in the name of Olinthus Gregory (his Christian name is the Greek word for a kind of wild fig). Forty years younger than Hutton, he hailed from Yaxley in Huntingdonshire and manifested early interests in both theology and mathematics. Unwilling to subscribe to articles of religion, he could not matriculate at an English university. But by 1798 he was living in Cambridge, working as a bookseller and probably doing some private teaching of mathematics. Rumour had it that his unpublished treatise on the slide rule impressed Hutton; he also proposed and answered questions in The Ladies’ Diary.

Olinthus Gregory.

When Charles Wildbore died in 1802, Hutton recommended Gregory to the Stationers’ Company as his successor, making him editor of The Gentleman’s Diary and probably also of the successful comic almanac Old Poor Robin. In the same year he became second assistant mathematics master at the Royal Military Academy. Thereafter he was beyond doubt the crown prince to Hutton’s mathematical kingdom. He translated papers for the Abridgement. Together with William Mudge he did work with ballistic pendulums at Woolwich in 1815–17, taking some of Hutton’s results further and promoting their adoption in practice. He was involved in testing a proposal to reduce the windage of cannon, which arose directly from Hutton’s own ballistics work and suggestions.

When Hutton at last retired from his own work on the almanacs in 1818, Gregory took on both The Ladies’ Diary and the role of general superintendent of almanacs. Like Hutton, he used the position to dispense mathematical patronage; like his mentor, too, he was admired for the use he made of the Diary to promote mathematics and educate the talented young.

Gregory also continued with his own independent work: a trigonometry primer in 1816 and a dissertation on weights and measures published the same year; the ambitious, eccentric Pantologia, a twelve-volume dictionary and encyclopedia of ‘Human Genius, Learning, and Industry’, in 1808–13. In 1823 he would determine the velocity of sound experimentally. Meanwhile he continued to write on theology. His career culminated with his role in the foundation of the non-denominational London University in 1827. He became professor of mathematics at Woolwich in 1821, and in due course the Stationers’ Company awarded him a handsome pension for his work on the almanacs. Charles Knight, nineteenth-

century promoter of learning reform, gave him an entry in his biographical study of great men.

It was a trajectory with which Hutton could of course identify, and he could take justified pride in the fact that Gregory owed much of his initial rise to his own help. The Academy, the almanacs and even Hutton’s publications were safe in his hands.

More could be done, though, and more directly than merely appointing a sort of intellectual heir and executor. Hutton also worked to secure his legacy through his publications, and a significant proportion of his time was taken up with preparing edition after edition of each of them, and seeing those new editions through the press.

The Tables, the Mensuration, and even his first book the Guide were all proving long-lived, and many a school relied on the last two for instruction. Indeed, unsually for an author on technical subjects, Hutton enjoyed a significant income from the sale of his books: he referred with some pleasure to the ‘liberal encouragement of the Public’ as a source of the means he now enjoyed. The Guide was ‘held in high estimation’ and was named in many a school curriculum around the British Isles in the early nineteenth century. The Mensuration was ‘the most complete work on the subject ever published’ according to the Edinburgh Annual Register, and remained a standard reference in the classroom as well as elsewhere. The Tables, too, had established themselves as such a standard that when one of Hutton’s correspondents reported on the forthcoming appearance of a rival work he suggested it would be little more than ‘an inaccurate transcript’ of Hutton’s.

And it was not only in Britain that his works were valued. Hutton was living proof that the British mathematical tradition was viable as an export product. A version of his Guide was one of the first accounts of bookkeeping to be printed in America (at Philadelphia, in 1788), and there were many subsequent American editions, variously transformed. His Course was adopted at West Point Military Academy from its opening in 1801, its contents becoming the basis for the mathematical course taught there. Robert Adrain, professor of mathematics at that academy, thought the Course ‘one of the best systems of mathematics in the English language’, and in 1812 he published an American version, with notes and other changes, condensing, reorganising and correcting.

West Point also had a copy of the Dictionary in its library, and that book, too, received the compliment of an American edition – of sorts. In 1817 one Nathan S. Read published An Astronomical Dictionary whose title page admitted with disarming frankness that it was ‘compiled from Hutton’s Mathematical and philosophical dictionary’.

If the English-speaking world appeared to have been conquered by Hutton’s work, what of that harder market to crack, the French? Here the story is a more explosive one, since France was an enemy state from 1793. Just before that date, an unknown translator made a French version of Tract IX from the 1786 Tracts, Hutton’s second published account of his ballistics work. Apparently it was done at the request of the chemist Guyton de Morveau. A story also circulated – even if untrue, the fact that it was plausible speaks volumes – that the great mathematician and astronomer Joseph-Louis Lagrange was working in Paris on Hutton’s writings about ballistics. Report said that Lagrange, born in Turin, had been under threat of deportation in 1793, but was allowed to stay, again at the request of Guyton (who was a member of the Committee of Public Safety as well as a chemist), because he was doing work of national importance. What work was that? He was ‘examining Hutton’s Treatise on Artillery’.

Neither the translation nor Lagrange’s response to the ballistics work was published. But in 1802, while the material remained unpublished in English, a French colonel named Villantroys got hold of the first part of Hutton’s final discussion of his ballistics work and translated and published it in Paris. What the background was to this, we don’t know; Hutton disapproved of the conduct of the war, but it seems incredible that he, an employee of the Board of Ordnance, could have deliberately supplied unpublished research on artillery to an enemy state. (Yes, for a few months in 1802–3 France was not at war with Britain, but Hutton was no more naive than the next person about the wisdom or the longevity of the Peace of Amiens.) Did Villantroys steal the text or have it stolen? I wish I knew.

Later still, printed works by French experts on artillery began to quote from and use Hutton’s results. Charles Dupin included an illustration of the ballistic pendulum and Hutton’s improved eprouvette in his 1820 Military Force of Great Britain; Antoine-Marie Augoyat quoted Hutton’s work the following year in his Mémoire sur l’effet des feux verticaux. Jean-Louis Lombard’s translation of Benjamin Robins’s work on gunnery contained a summary of Hutton’s 1778 results. A French reviewer called Hutton ‘as commendable for his observational talents as for the scientific methods he has used’ to analyse the results, praising the thoroughness and consistency of his work. An English reviewer remarked, in turn, on how the French ‘so eagerly possess themselves of every essay, investigation, and experiment of Dr. Hutton on the subject, as soon as it is made public’.

Both the American and the French uses of Hutton’s work, gratifying though they were, bordered on piracy; editions in New York or Pennsylvania were most unlikely to have Hutton’s explicit approval (or that of his British publishers), and the French version of the ballistics work he could not have avowed and may not even have known about. In part, Hutton’s work was simply being absorbed into the common stock of knowledge. But there was such a thing as decency, and when, for instance, one Alexander Ingram in 1796 ‘corrected and enlarged’ the Guide he was most likely taking gross advantage of Britain’s lack of effective copyright protection. The same could be said of the apparently unauthorised Keys to the Course concocted by Daniel Dowling in 1818 and to the Measurer by J.M. Edney in 1824.

If Hutton could do little or nothing about the activities of American and French editors, printers and spin-off authors, he could certainly address the question of home-grown piracy by keeping up his own steady stream of re-editions of his most popular works. By the time of his retirement in 1807 there had been fourteen authorised editions of the Guide, twelve of the Mensuration and the Measurer, four of the Tables and five of the Course.

In order to keep readers buying these new versions, and keep them away from the unauthorised rivals or the work of his colleagues, Hutton was careful to make small but significant changes every time. Hardly an edition of his was without a few changed examples, improved explanations, minor reorganisation or rewriting, or insertions of new matter. The books, indeed, took on something of the character of permanent works-in-progress, the Course in particular functioning as a site to try out and announce new ideas, for instance in the theory of materials, the subject of ongoing experimental work at Woolwich. The Mensuration eventually became so altered and enlarged with new definitions and new figures as to be ‘almost a new work’. Tables grew larger; examples were re-computed. Hutton welcomed suggestions from readers – of the Guide he had said in 1786 that ‘Any hints of improvements that may be made, either in the Arithmetic or the Key, and addressed either to the author or publishers, will be attended to in the future editions of them.’

The same was at least implicitly true of all his books. From time to time Diary contributors, in particular, would offer suggestions for improvements to Hutton’s textbooks, correcting errors or modestly proposing an improved example or a changed order of presentation. To the Recreations were added titbits from readers including a long and eccentric correspondence about divining rods, interesting less for its content than for the fact that the enthusiast who wrote to Hutton on the subject was Lady Milbanke, afterwards Lady Noel, Byron’s mother-in-law and grandmother of Ada Lovelace. The Dictionary, too, was a particularly natural site in which to collect new material from readers and elsewhere, to reorganise and perfect, with in this case a still more obvious eye to Hutton’s intellectual legacy, his stewardship of a particular world of mathematical culture and achievement.

Biggest of all was naturally the contribution of Olinthus Gregory.

In 1811 a third volume of the Course was added to the original two, and although Hutton’s name was on the title page it was acknowledged in a preface that Gregory had collaborated on the volume with his mentor and friend. The new volume dealt with conic sections, calculus, trigonometry, the solution of equations and various practical subjects including methods of surveying, the effects of machines and the pressure of earth and fluids. There was a summary of Hutton’s work on ballistics as well as his customary concluding selection of questions. The intention was to deal with recent changes and improvements in the curriculum at Woolwich; but, as even Hutton tacitly admitted, the effect was somewhat miscellaneous. It tended to make the Course as a whole harder rather than easier to use in teaching, since much of what was in volume 3 really needed to be split up and inserted within volumes 1 and 2: it ‘may best be used in tuition by a kind of mutual incorporation of its contents with those of the second volume’, he admitted. The Course would have to wait several more years before posthumous editions effected the reorganisation and rationalisation it needed.

About one particular part of his printed legacy Hutton became perhaps disproportionately obsessed. His work on the density of the earth, he became convinced, was in danger of being neglected, overshadowed, forgotten because of what had happened since. What had happened was partly his row with the Royal Society and the tendency of mathematicians generally to become invisible there, denied fellowship or publication. It had also happened that Banks’s friend and supporter Henry Cavendish had devised a new, wholly different way to measure the strength of gravitational attraction and hence the density and mass of the earth.

Gunpowder and Geometry

Gunpowder and Geometry